OUT OF THE PAST: EPISODE 11

- Brooke

- Oct 19, 2019

- 9 min read

The Oak Grove Jane Doe

Original news articles:

Over the course of a few months in 1946, several people got the scares of their lives when they stumbled upon different parts of a woman whose remains had somehow ended up uncomfortably far from each other. The crime, which some dubbed “The Wisdom Light Murder,” was one of the most infamous in Oregon during the twentieth century. This week on Out of the Past: The Oak Grove Jane Doe.

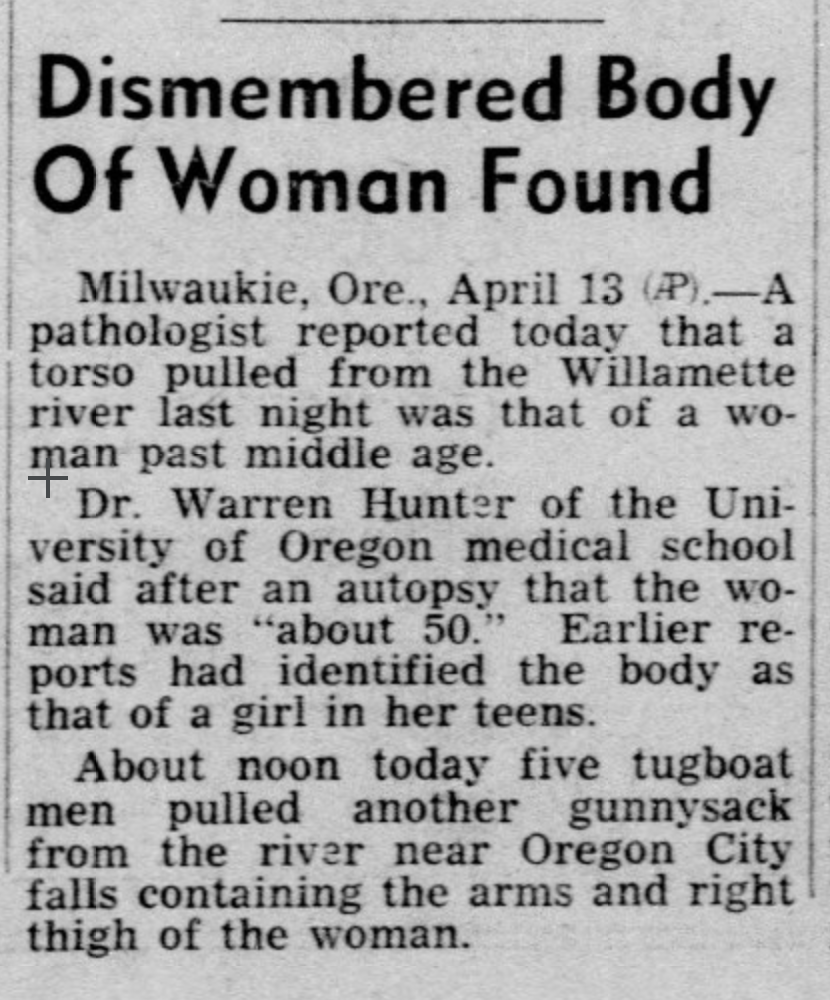

The first discovery happened at 8 o’clock in the evening of April 12th, 1946. A group of friends, H.C. Foster of Portland and James and Mary Rader of Milwaukie, were taking a stroll down a trail near the Wisdom Island moorage on the east bank of the Willamette river when they saw something floating in the water. It was wrapped in burlap, and reeked with the odor of death. The friends became concerned that someone had wrapped up a litter of kittens and dropped them in the water to dispose of them. Already morally outraged, they opened the burlap to reveal the body of a woman. Not her whole body, just her torso. There were burn marks on the lower part of the torso that examiners hypothesized might have been caused by a blowtorch, suggesting that the victim was tortured. The Portland Oregonian reported that “the nude torso was wrapped in brown slacks, a dark blue sweater, long union suit underwear and a grayish-black tweed topcoat.” The burlap and the clothing had all been bound together with tape, rope, and telephone wire.

Almost immediately after the story hit the papers the next day, another gruesome discovery was made. Five tugboat operators found a similar burlap package about six miles from where the victim’s torso was found. This one, containing her right thigh and both of her arms (but no hands), was bound with phone wire just like the first one, and in addition it was weighed down with sash weights. The men explained to law enforcement that they had seen the package floating there for at least a month, but didn’t think to take a closer look until they had read about the previous day’s discovery.

Authorities thought this might be all they would find of the woman, but in July, her left leg was found floating under the Oregon City Bridge. A bundle of what was thought to be the woman’s clothing was also found around this time.

Early in September, part of a scalp was discovered, again in Oregon City, and in October, the victim’s eyeless head was found near where the torso had originally been found back in April. This was enough for the medical examiner to determine that she’d died of blunt force trauma to the head. Her hands and feet were never located.

The investigation got off to a rocky start. Clackamas County Coroner Ray Rilance, who examined the first set of remains, made some incorrect assumptions: for example, he thought the victim was a very young woman, possibly in her teens. This made parents in the area with missing daughters start hounding the police station. Then, a more experienced pathologist from the University of Oregon, Dr. Warren C. Hunter, determined that she was “50 years of age or older.” Rilance also made the tactless statement that the killer had done “rather a neat job” cutting up the body, and that “at least he knew where the joints were.” Deputies on the scene at first erroneously identified the severed arms as legs.

Shortly after the first bag was found, there was a promising development: sets of footprints were found leading down to the river very near to where the remains had turned up. The prints were about a month old, but they were the only ones in the area, and near them was a “Sko-Pal” brand rabbit feed bag—the same kind that the torso was wrapped in. The prints were those of a male who wore about a size 10 shoe. Nothing more came of this, however.

A 29-year-old man named Orville A. Switzer called the police claiming to “know all about the torso murder case,” and he was arrested, but he turned out to be a crank. A couple of days after he was released, he went up on vagrancy charges and received a 270-day jail sentence.

From this point on, the investigation mostly consisted of working with the weather bureau, trying to find where the assailant originally dumped the packages into the water. They tried to calculate things according to the speed of the current and how long she’d been in the water. This ultimately did nothing to help them move forward in the investigation. In early September, they began trying to draw a connection between the victim and a missing woman from Seattle named Marie Nastos. This proved to be a dead end when Nastos’ husband revealed that Marie had had an appendectomy some years earlier. The torso in the river still had an appendix.

Nastos was the closest anyone got to a working theory about the victim’s identity at the time—at least as far as we can tell from the news stories that survive. In fact, none of the sources I’ve seen on the internet even seem to reflect that she was eventually ruled out. It’s easy to see why: I almost missed the tiny article in the Oregonian that reported her elimination as a relevant link in the case when I was scrolling through microfilm. As the years have elapsed, however, several names have come up that were at one time or another considered, and as we’ll see, some of them seem plausible.

Eva Linder Panko met her husband while working on the homefront during WWII. Neighbors reported hearing violent fights coming from their residence nearly every night, and they separated after ten months. Subsequently, Eva purchased a house with her coworker Herbert Troy Dennis. The house burned to the ground not long afterward—at the same time that Panko disappeared. It was soon established that the fire was set intentionally in order to collect insurance (though there was never any payout). Police located Dennis in Illinois, and it came out that he and his brother were ex-cons. The main argument against her being the body in the river is that she had a glass eye, and medical examiners were fairly confident that Oak Grove Jane Doe had both her eyes at the time she was killed, though they were gone by the time her head was found.

Marie Diffin had been missing since September 1944, when she left her husband and ran off with two men. Her husband waited until 1950 to call the Portland authorities and tell them he thought she might be the woman who ended up dead in the river, as he had heard rumors that she had gone to Portland, and that she was known to frequent bars there. The obvious question was why he waited so long to report this. He said that his and Marie’s daughter Coleen told him if he didn’t she would. When police questioned Coleen themselves, as well as Marie’s parents, they found that everyone suspected foul play. Coleen was sure of it. She said that if her mother wasn’t dead, she was sure she would have heard from her for the sake of her youngest son. Diffin’s sister also seemed positive she was dead. She described Mr. Diffin as a liar with a terrible temper. Marie's parents claimed that her husband told her if she left, he’d kill her. One of the men who ran off with her in 1944, George Hart, said the last time he saw her was when she and the other man, Carl Schulz, said they wanted to go somewhere so far nobody would ever find them, maybe Mexico. The biggest problem with Marie as a candidate is that she would only have been in her mid-thirties at the time of the Wisdom Light discovery. She was also reported to have a large tumor on her shoulder from which some people close to her said they were sure she would soon die. No sources anywhere suggest that the torso in the water had a matching tumor.

Marian Coffey, like Diffin, was a married woman with a jealous husband. She loved the nightlife and was said to be at a different bar every night. On April 16, 1946, her husband came into one of her local hangouts with the article about the torso being found in the river. He said that he thought it was Marian. He even went to the police station, and when they let him look at her personal effects, he positively ID’d them. She had disappeared on March 18, he said: he went to work, came home, and she was missing. Coffey denied ever having abused his wife, but he spoke very poorly of her, complaining about her loose behavior to anyone who’d listen. Theoretically, it would have been possible to identify the victim if she was indeed Marian Coffey: according to Mr. Coffey, she had had part of her uterus removed because of a tumor. But there is no information available on whether this was true, or if the torso was ever checked in light of this claim.

Bessie Carol Nevens was reported missing in a handwritten letter to the police by her sister, Mrs. J.L. Wilson, who said that she had disappeared in 1943 with a man who said he was taking her to Oregon. The day before Nevens’ disappearance, Wilson was contacted by someone who wanted an address for Bessie, claiming that her Navy-deployed husband wanted to send her some funds. This was out of character for her husband, and when Mrs. Wilson called the Navy the next day, they claimed to have no record of Bessie’s husband attempting to contact her. Bessie was a close match for the physical description of Oak Grove Jane Doe, both in age and appearance. But since the missing person report came from LA and was out of the Portland Police Bureau’s jurisdiction, they tried to shrug it off. Records indicate that the police did not look further into this theory, but neither did they conclusively rule Bessie out.

JD Chandler and Theresa Griffin Kennedy suggest in their 2016 book Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland that the victim is a woman named Anna Schrader. She had a long history with the police department and even worked as an undercover agent in the 1920s. She was rumored to have had an affair with Lieutenant Bill Breuning (both parties were married). Supposedly, in 1929, when their relationship went sour after he refused to leave his wife for her, Schrader laid in wait for him outside his house with a gun, and they got into a violent altercation in which he broke her ribs. The aftermath was long, complicated, and bitter. There were multiple court cases. Schrader exposed her affair with Breuning, and he lost his job. She also threatened to expose various members of the police department for corruption. She gradually faded out of public view until a few days before the time of the torso discovery in April 1946, when an ad appeared in the Oregonian seeking information on her whereabouts. No one ever saw Anna Schrader again .

Chandler and Kennedy make a compelling case, one I find pretty persuasive, but of course it’s just another theory, and we are no closer to knowing who the Oak Grove Jane Doe is today than we were three quarters of a century ago.

It’s devastating that this woman was not only murdered, but lost her identity. People that knew and loved her never got to pay respects because you can’t identify next of kin to inform when you can’t even identify the victim. People probably walked around with holes in their hearts for the better part of a century, not sure what had happened to their loved one.

Luckily for us, a society ready to enter the 2020s, we have technology at our service that in many cases can help us identify victims quickly. It can give names to victims who have been nameless for decades, and that’s amazing. Just this year, two of the Bear Brook victims were able to be identified, when just a few years back they weren’t sure if they could even get a viable sample from the remains.

Unfortunately for Oak Grove Jane Doe, there are no remains for law enforcement’s new technology to examine. All the evidence from her case was lost sometime in the 1950s, just within the decade after her death. It’s upsetting to think that she will likely go without an identity for the rest of human history. Most people have already forgotten her story. It’s almost entirely faded into the past.

If you would like to help other victims like the Oak Grove Jane Doe regain their identities, I would recommend making a donation to the DNA Doe Project. Just in the last year or so they’ve been able to identify infamous Doe victims who had previously lost their names, including The Buckskin Girl, Joseph Newton Chandler, and Orange Socks Doe. They do great work.

That's all for this week. I'll see you next time on Out of the Past.

Comments